Rainbow

with Egg

Underneath and an Elephant

Shampoo

index

Monthly Film Bulletin

Roger Ebert - Chicago Sun Times Review

Pauline Kael Review

Shampoo

U.S.A., 1975

Director: Hal Ashby

MONTHLY FILM BULLETIN

Volume 42, Nos. 492-503

by RICHARD COMBS

Cert--X. dis--Columbia-Warner. p.c--Persky-Bright/Vista. A Rubeeker production. p--Warren Beatty. assoc. p/p. manager--Charles H. Maguire. asst.d--Art Levinson, Ron Wright. sc--Robert Towne, Warren Beatty. ph--Laszlo Kovacs. col--Technicolor. ed--Robert Jones. p.designer--Richard Sylbert. a.d--Stu Campbell. set dec--George Gaines. set design--Robert Resh, Charles Zacha. m--Paul Simon. orchestration--Pat Williams. cost--Anthea Sylbert. sd. ed--Robert Knudson, Robert Glass, Dan Wallin. sd.rec--Dennis Jones. sd.re-rec--Tom Overton.

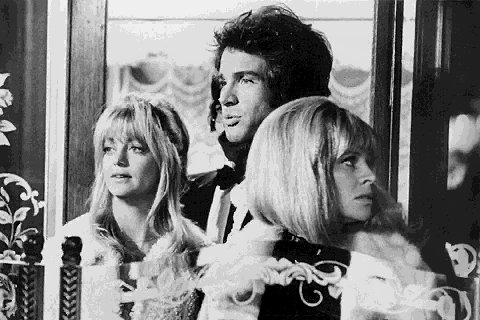

I.p--Warren Beatty (George), Julie Christie (Jackie Shawn), Goldie Hawn (Jill Haynes), Lee Grant (Felicia Karpf ), Jack Warden (Lester Karpf ), Tony Bill (Johnny Pope), Carrie Fisher (Lorna), Jay Robinson (Norman), George Furth (Mr Pettis), Jaye P. Morgan (Tina), Ann Weldon (Mary), Randy Scheer (Dennis), Susanna Moore (Gloria), Mike Olton (Ricci), Luana Anders (Devra), Brad Dexter (Senator East), William Castle (Sid Roth), Jack Bernardi (Izzy), Doris Packer (Rosalind), Hal Buckley (Kenneth), Howard Hesseman (Red Dog), Michelle Phillips (Girl on Sunset Strip), Cheri Latimer (Girl in Car), Susan Blakely (Girl on Street) 9,889 ft. 110 mins.

November 4, 1968, the eve of the Presidential elections. George, a Beverly Hills hairdresser, has plans to open a beauty shop of his own; refused a bank loan, he is given an appointment with wealthy financier Lester Karpf through the latter's wife Felicia (with whom George is sleeping). Harassed at work by his petulant employer Norman, and then by his steady girlfriend Jill Haynes, who tells him that she has been offered work on a commercial to be made in Egypt, George later meets Karpf. and in his office encounters Jackie Shawn, an old girlfriend of his and now Lester's mistress. Lester asks George to an election party that evening to discuss business, and also asks him to bring Jackie; George visits Jackie to do her hair, and they are on the point of making love when Lester arrives. Later visiting Felicia, George is first seduced by her teenage daughter Lorna. That night at the party, Jackie becomes embarrassingly drunk and is eventually taken away by George; Felicia denounces Lester for being unfaithful with Jackie and leaves him to return with Jill and her escort Johnny Pope (director of the commercial), who drive on to a party already attended by George and Jackie. Seen making love with Jackie by Jill and Lester, George chases after Jill, who goes to Johnny's place and in the morning tells George their affair is over. George returns home to find Lester there with two thugs; George persuades him that his casual affairs are meaningless, and Lester leaves open the possibility of a business deal. George visits Jackie to propose marriage, only to be told that she is going off with Lester, who is getting a divorce from Felicia. George disconsolately watches the two drive away.

The principal sophistication of Shampoo - indeed the major ploy round which its casual jigsaw of social comedy is built - is never to allow its general and personal themes (taking election night, 1968, as a social, moral and political watershed) to intertwine too closely or too obviously. In their very separation in fact, the film seems to envisage that cynicism and erosion of all moral and political philosophies that it takes to be characteristic of the age: of the assorted 'swingers' who come together on this night for some sort of personal reckoning, only the businessman, Lester, seems even to notice the political event taking place, and by the end having made his peace with the man who has cuckolded him, with both his wife and his mistress, he is the only one to respond to the victorious Nixon on TV: "Maybe Nixon will be better, I don't know they're all a bunch of jerks ... I don't know what to do anymore ..." The strategy compares interestingly with Robert Towne's screenplay for Chinatown, where Los Angeles in the Thirties can still be seen as a kind of Eden, and even the seediest of its inhabitants as relatively innocent. The political plot intrudes on the setting like an inevitable and irresistible desecration; in Shampoo, a general debasement is taken for granted, and instead of converging for a paradigmatic conclusion similar to Chinatown, the various strands of individual lives and national politics simply go on unravelling ("Bring us together" is a slogan heard in the Nixon TV broadcasts that briefly and ironically illumines the discrete levels of the plot). Symptomatic of the new confusion is the fact that the nearest equivalent here to Chinatown's Noah figure, Lester, is the most sympathetic (and, as played by Jack Warden, the most exactly sketched and placed) character - the paternalistic businessman as much adrift as anyone, and the only individual in whom wayward impulses and ideals still exist in any tension. The film tacks with supple humour over the competing allegiances and personal safe-guards established by all the characters; but one of the disadvantages of the looseness with which it deploys its conceits is that it is constantly in danger of losing its grip on them. The modest, self-effacing style adopted by Hal Ashby for The Last Detail, and perfectly appropriate to its picture of liberating adventure headed up the blind alley of routine and comforting anonymity, here provides too slack and toneless a context for the comedy, giving in to more than it shapes the performances. As producer and co-writer as well as star, Beatty has provided himself with not so much a part as a forum: his excavation (and condemnation) of his own casually amoral screen persona is itself too carefully safeguarded in the appealing little-boy-bewildered expression he wears throughout, and in some conspicuously random Method exercises (his display of rage after being refused a bank loan; his final, halting explanation of his life-style to Goldie Hawn). Where Beatty's performance often spills indulgently over his role, other players (Julie Christie, for example) seem entirely misplaced in the Los Angeles setting or, like Goldie Hawn, more evidently and glibly fill a need for a certain kind of humour than they fit too well into character. Like Steelyard Blues, Shampoo has the bursting-with-talent but fuzziness-of-effect aspect of a movie made by a group of friends for their own amusement, its metaphors for America have a similarly rough and ram-shackle look. It also follows the current trend of transforming grief at the souring of the American dream into something cooler and more archaeological in its concerns. As such it is not an uninteresting artefact, but without the allegorical complexity of Chinatown or even the nostalgic enthusiasm of American Graffiti, seems confined to a fairly superficial level.

Shampoo

US (1975): Drama/Comedy

Roger Ebert Review: 2.5 stars out of 4

Beverly Hills, Nov. 4, 1968. In 24 hours, Nixon will be making his victory speech on television, pledging an open administration. In 40 hours, George, a hairdresser, will have negotiated the ruins of three affairs, bedded tentatively with a possible new recruit and seen the wreckage of his delusions. SHAMPOO never quite connects its images of national mediocrity and personal self-deception, but maybe it doesn't need to; maybe the message is that in a nation that doesn't trust authenticity, what you get is a Nixon in the White House and a stranger in bed.

George is played by Warren Beatty as a star Beverly Hills hairdresser ("The heads come to me") and sexual athlete. He makes love cheerfully with various clients, not so much because he's promiscuous as because he's driven, and always has been: "As long as I can remember, when I see a pretty girl and I go after her and I make her, it's like I'm gonna live forever." It's a sunny vision, but during the crowded hours covered in SHAMPOO he gets too many pretty girls and too many private lives mixed up, and is left facing a future without the woman he (possibly) really does love. That his future also contains Nixon and Agnew is something he never reflects on and perhaps has not noticed; he moves through a thicket of news broadcasts and election-night parties totally engrossed in his own confusions.

He's living with Jill (Goldie Hawn), a wide-eyed and rather simple creature who naively believes she has him to herself. Jill's best friend is Jackie (Julie Christie), who knows a lot better. Jackie and George and Jackie had an affair going at one time, and they return to it occasionally, but at the moment Jackie is being kept by Lester (Jack Warden), an orange-haired tycoon with vaguely sinister connections. Oh, and Lester's wife Felicia (Lee Grant) is one of George's clients down at the salon and in bed. George also succeeds, during the course of the film, in seducing or being seduced by Lester's daughter, so he has the poor guy surrounded.

The sexual gymnastics aren't the movie's point, however, and the sex scenes are never developed in an erotic manner. They're directed by Hal Ashby more as symptoms of George's dilemma, which is that he likes being loving and kind, he listens to his clients and sometimes even really does care about their problems, but in some final way he's too blocked to develop a deep relationship, to really give himself. At the end, when he tries, when he proposes marriage to Jackie, it's too late and his proposal is doomed anyway—because Lester's Rolls-Royce and a marriage in Acapulco are waiting, and George should have known Jackie was that sort of person in the first place.

SHAMPOO is a movie I expected to admire enormously, but the movie didn't quite work for me. Its timing wasn't confident enough to pull off its ambitious conception. It wasn't as funny as it could have been in the funny places (as when Lester speculates that George is gay). It isn't as savage as it could have been in its satire (a Nixon crowd's election-night party bogs down in a pointless series of what sounds like college yells from a U.S. senator, whose behavior is so implausible it doesn't work as anything). And it's not as poignant as it could be in its moments of truth, because we can see the wheels turning. We can sense that the movie's providing obligatory scenes instead of engaging us in a series of discoveries about its characters.

Still, as an artifact of the Hollywood climate in 1975, SHAMPOO inspires nostalgia for a time when sexual and political positions could be staked out in a mass-market movie. Compare this film with Beatty's 1994 LOVE AFFAIR, which is also about a compulsive womanizer, and you'll perhaps wonder: Could SHAMPOO have been made in the 1990s? (And would LOVE AFFAIR have been laughed out of the 1970s?) LOVE AFFAIR is better than SHAMPOO at doing what it sets out to do, but for such questions, that's beside the point.

Shampoo

US (1975): Drama/Comedy

Pauline Kael Review

This sex roundelay is set in a period as clearly defined as the

jazz age--the time of the Beatles and miniskirts and strobe lights. When

George (Warren Beatty), the hairdresser hero, asks his former girlfriend,

Jackie (Julie Christie), "Want me to do your hair?," it's his

love lyric. When George gets his hands in a woman's hair, it's practically

sex, and sensuous, tender sex—not what his Beverly Hills customers are

used to. The film opens on Election Eve, November 4, 1968, and ends the

day after Nixon and Agnew's victory; it deals with George's frantic

bed-hopping during those 40-odd hours, in which he tries to borrow the

money to open his own shop, so he can settle down with his current

girlfriend, Jill (Goldie Hawn). The script by Robert Towne, with the

collaboration of Beatty (who also produced), isn't about the bondage of

romantic pursuit—it's about the bondage of the universal itch among a

group primed to scratch. The characters (the others are played by Jack

Warden, Lee Grant, Tony Bill, and Carrie Fisher) have more than one sex

object in mind, and they're constantly regrouping in their heads. When

they look depressed you're never sure who exactly is the object of their

misery. The director, Hal Ashby, has the deftness to keep us conscious of

the whirring pleasures of the carnal-farce structure and yet to give it

free play. This was the most virtuoso example of sophisticated,

kaleidoscopic farce that American moviemakers had yet come up with;

frivolous and funny, it carries a sense of heedless activity, of a craze

of dissatisfaction. With Jay Robinson, George Furth, Brad Dexter, William

Castle, and, in a bit, Susan Blakely. Cinematography by Laszlo Kovacs.

Columbia.

For a more extended discussion, see Pauline Kael's book Reeling.