Rainbow

with Egg

Underneath and an Elephant

Harold and Maude

REVIEWS

Monthly Film Bulletin

Screens

Premiere

Roger Ebert - Chicago Sun Times

Pauline Kael

CineBooks

Audio Clips from Harold and Maude

Cert--.AA. dist--Paramount. p.c--Paramount,/Mildred Lewis and Colin Higgins Productions. exec. p--Mildred Lewis. p--Colin Higgins, Charles Mulvehill. p. manoger--Wes McAfee. asst. d--Michael Dmytryk. sc--Colin Higgins. ph--John A. Alonzo. col--Technicolor. sp. ph. effects--A. D. Flowers. ed--William A. Sawyer, Edward Warschilka. a.d--Michael Haller. set dec--James Cane. m/md--Cat Stevens. song-- "If You Want to Sing" by Cat Stevens. sd. ed--James A. Richards. sd. rec--William Randall. sd. re-rec--Richard Portman.

l.p--Ruth Gordon (Maude); Bud Cort (Harold), Vivian Pickles (Mrs Chasen). Cyril Cusack (Claucus), Charles Tyner (Uncle Victor), Ellen Geer (Sunshine Dore), Eric Christmas (Priest). G. Wood (Psychiatrist), Judy Engles (Candy Gulf), Shari Summers (Edith Fern), M. Borman (Motorcycycle Cop), Marjorie Morley Eaton (Madame Arouet), Ray Goman and Gordon Devol (Police Officers), Harvey Brumfield (Cop), Henry Dieckoff (Butler), Philip Schultz (Doctor), Sonia Sorrell (Head Nurse), Margot Jones (Student Nurse), Barry Thomas Higgins (Intern), Pam Bebermeyer and Joe Hooker (Stunt Doubles), Susan Madigan

8,260 ft. 92 mins.

Harold Chasen, the quiet son of a wealthy and dominating mother, has no friends and only one interest - a calm fascination with death. His frequent and very realistically staged mock suicides and his penchant for attending funerals in his own hearse are a sore trial to both his mother and his psychiatrist. He meets another regular funeral-goer, an elderly woman called Maude, who takes him back to the abandoned railway carriage where she lives with her memorabilia and introduces him to her philosophy of always seeking the new experience. Harold's mother has meanwhile replaced his hearse with a snappy sports car and decided to introduce her son to responsibility through marriage. But a succession of likely prospects sent by a computer dating service is put to flight by Harold's gruesome sense of humour; and an attempt to have Harold drafted into the army by his Uncle Victor is similarly defeated with Maude's assistance. Harold converts his Jaguar into a smallish hearse and continues to spend his time in the liberating company of Maude, eventually sleeping with her and then announcing to his shocked mother that he intends to marry her. But Maude has plans of her own, including a theory that life should end at eighty, and on her birthday blissfully takes an overdose of sleeping pills. At first distraught, Harold seems on the point of driving his hearse over a cliff, but it only turns into another mock attempt and he walks away, free at last to lead a life of his own.

In a spirit of anything goes, which was also very

characteristic of The Landlord, Hal Ashby plays the high absurdity of

Harold and Maude on all the stops of farce, satire, black comedy and

lyrical eccentricity. It is not that he is not fully in control of his

material since Ashby has a style and a device (colour contrasts and

exposure changes, gauzes and some edgy editing) to suit perfectly all the

changes in tone and content. But if everything fails to clinch as

successfully as it did in The Landlord, it is because the movie fails to

hold firm, or rather splits unhelpfully in two directions. Harold Chasen

shares with Elgar Enders in The Landlord a privileged and sheltered

upbringing, but his compulsion to play games with his own death (the first

scene discovers him quietly preparing another attempt, to be found by his

mother hanging from the ceiling, face pale and straining, and dismissed

with a brisk "I suppose you think that's very funny, Harold'') is

something other than a wish to commit social outrage. The early black

comedy is so effectively grotesque simply because Harold is the dominated

son reduced to the most pathetic puppet: he is somehow less than alive,

waiting for a magic spell to provide the necessary spark. On comes the

fairy godmother (Ruth Gordon, all wrinkles and grimacing mannerisms, to

match perfectly Bud Cort's cherubic, doll-like tranquillity), and she

talks to him of other times, other lives, other visions ("I don't

miss the kingdoms, but I do miss the kings'). The spell works for a while

- and so effectively that when the time comes for Harold to have sex with

Maude questions of tact or good taste hardly seem broached. Maude after

all, in best fairy godmother fashion, will vanish as predicted on her

eightieth birthday, and Ashby provides further insulation in satirising a

battery of Establishment reactions: from the psychiatrist rather peeved

that Harold, instead of fulfilling the boyish dream ('quite common,

especially in our society") of sleeping with his mother, has gone one

better to sleep with his grandmother, to the churchman who works up some

equivocal revulsion imagining "Your firm young body commingling with

her withered flesh". But the film then proceeds to run through such a

conventional litany of liberated emotions (idylls in the park, stealing a

car, saving a tree) that Harold the person seems to be not merely Harold

the puppet revived but something altogether different, a borrowing from

more facile forms of entertainment; and one feels little confidence, or

interest, in the individual who strides off at the end to the

accompaniment of Cat Stevens' song "If you want to be free - be

free!" The best scenes - almost always when the ogre of Harold's

mother is around - combine Ashby's flair for social comedy and a peculiar

sense of the conjuring trick that Harold is trying to pull off with his

sham suicides. He describes for Maude the time when it was thought he had

been killed in an accident at school and how he watched his mother's

reaction to the news, a well-bred theatrical gesture, and how ever since

he has enjoyed playing at his own death and, presumably, by his

theatricals tried to shame a real reaction from his mother. The joke is

adroitly turned against Harold when he attempts to scare off one of his

mother's proposed dates with a realistic demonstration of harakiri only to

have her, a Method actress by profession, outdo him in delighted death

agony.

BACK TO TOP

BLACK MAGIC

Harold and Maude is a very funny film all about death. Richard Buskie

explains why he thinks the black comedy is worth another viewing

SCREENS

Issue 5, 1987

by RICHARD BUSKIE

When Harold and Maude was released by Paramount in 1971, it was considered by industry insiders and film critics alike to be of curiosity value; a small offbeat black-comedy, with appeal mostly limited to those harbouring an unconventional taste for the tasteless.

Time - and millions of viewers - were to prove this assumption wrong, however, as the film's popularity spread first among college students across America and then throughout the general movie-going public on both sides of the Atlantic.

Today, after several cinematic re-runs, numerous television screenings and its release on video, Harold and Maude enjoys a very substantial cult status.

What sets this film apart from so many other black comedies is the way in which it deals with its morbid - and often downright sick - subject matter with a well-balanced combination of humour, pathos and sensitivity. It is a funny film with a message, without being pretentious.

NECROPHILIA RULES

The story concerns itself with 20 year old Harold Chasen (Bud Cort), a classic poor-little-rich-boy, who is bored with life, bored with his mother's dominant and over-bearing nature, and whose sole source of escape is a sick preoccupation with death - necrophilia rules O.K.

Leisure time is spent as an onlooker at funerals (travelled to in his very own hearse), and his time at home is largely taken up with devising fake suicides to shock his mother and anyone else who might happen to be around. When Mrs Chasen sets him up with a trio of computer dates, Harold sees each of them off by variously pretending to set fire to himself, chopping off one of his hands, and performing hara-kari with a knife to the stomach. Mum looks on, unamused.

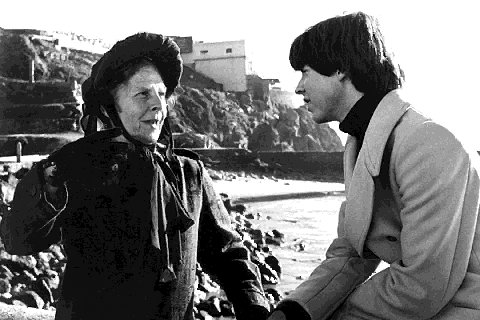

A complete turnaround in Harold's life, to say the very least, arrives in the pint-sized shape of Maude (Ruth Gordon) a wildly eccentric 79-year-old lady with a healthily bizarre and - seemingly - happy outlook on life. Harold befriends her after they meet at a couple of funerals, and within a short space of time the two become lovers. (An everyday tale of ordinary folk!)

Maude teaches Harold to search out the fun in life, to ignore the narrow-mindedness and the conventional rules laid down by society. Under Maude's tutelage, Harold comes out of his shell. He is very affectionate towards her, learns to dance and play the banjo, and is generally far more animated than when in the company of others.

Harold's mother, meanwhile, appalled when her little boy shows her a picture of his "fiancee", decides that what he needs is a spell of good old-fashioned army discipline. An interview is set up with Uncle Victor (excellently portrayed by Charles Tyner), a sadistic one-armed officer who frequently pulls his armless sleeve into a forthright salute, and who can be best described as a raving lunatic.

Even this maniac is revolted, however, when he witnesses Harold taunting an "old lady" (Maude), encouraging her to "drown" herself. Uncle Victor decrees that his nephew is too mean and violent, and therefore unfit for army life and so H & M proceed on their happy way.

Yet for all her apparent verve and happiness, there is clear evidence just beneath the surface that life has not been a bed of roses for Maude. Tears appear whenever she remembers her dear departed husband, and the numbers imprinted on her arm point to tales from the dark side in a concentration camp.

MAUDE TAKES POISON

Matters come to a head when, after celebrating her 80th birthday, Maude informs Harold that she is now ready to die and has taken poison in order to hurry this process up. She is rushed to the hospital but it is too late. Harold is naturally distraught, but for all this his spirit has been liberated and his life has been changed for the better.

Hal Ashby's direction of Colin Higgins' story is perfectly on target. While the preoccupation is with death, the film is also an unmistakable celebration of life. Clearly everyone, even Maude, has their own personal cross to bear, but one can still build joy out of heartache. Furthermore, Maude appears to accept death as the natural conclusion to - or even continuation of - life itself.

BEAUTIFULLY CONSTRUCTED

Many of the comedy sequences are also beautifully constructed. Aside from Harold's aforementioned phony suicides, (and these have to be seen to be believed), there are other assorted visual highlights, such as the scene in which a motorcycle policeman stops the couple after a tree has been stolen from outside a local shopping centre. While he prepares to read them their rights, Harold and Maude suddenly drive off. The cop takes out his gun, steadies himself, takes aim and fires ... but he has forgotten to load any bullets. Nine times out of ten this kind of sight-gag would be overly corny, but Ashby handles it brilliantly and the result is high comedy. So too is the sight of Harold's E-type Jaguar, a gift from his mother, revamped and converted into a small hearse.

Add to these ingredients acting of the highest order by

the entire cast - especially the understating Cort and the over-exuberant

Gordon - as well as Cat Stevens' catchy and upbeat theme song, and one has

a classic American film of the 70s.

BACK TO TOP

A Young Man and The Movie That Saved Him

PREMIERE

May 1993

by HOLLY SORENSEN

Amid the thick gray calm of Boston's Logan Airport, right next to one of the dozens of shops selling Cheers T-shirts, sits the Legal Sea Foods store and its big tank crawling with lobsters. Once you've made your selection, Mike Holland, the outlet's 30-year old manager, will fish it out of the murky water for you and pack it in an insulated box, with some seaweed that he guarantees will keep the lobster alive for up to a day. Holland is an expert at maximising survival.

Seventeen years ago, in the nearby suburb Lexington, Mike Holland says, he was "the star middle-child, Boy Scout, do-everything-your- mother-wants" ninth grader - until the day his physicist rather took the family to a therapy session and announced that he was leaving. That night, as his father packed a suitcase on the bed upstairs, Mike stood in the downstairs entry-way, screaming in vain for him to stay. "Afterward", Mike recalls, "I kind of went haywire: I got busted for stealing a car and for drinking." A year or so later, Mike drove up to his pretty white clapboard house and saw his mother's car, his aunt's car, and his brother's car all parked outside. "That's when I knew,'' Mike says. His father had been killed in a car accident. "Then I punched out all the glass in the door."

In the face of that avalanche of misfortune, it might be ludicrous to imagine one key event nudging someone through the grief process. But Mike Holland still remembers the night in 1977, when he and his friends went into Cambridge and wound up at the Harvard Square Theatre. There he watched the story of a depressed, death-obsessed young man who gets taught how to live, and then some, by a 79-year-old woman. Harold and Maude, he says, "kind of cleared everything up for me, made things a lot easier to deal with, as far as death is concerned." After that night, "I saw it maybe every six months, for the next few years. At least twenty times, I've seen that movie in a theater."

And he wasn't the only one. In the pre-video era, enough people in the Cambridge environs watched Harold and Maude and its fellow cult hit, King of Hearts, to keep the movies running in various local theaters for more than a decade. "It was simply a very different time," explains Justin Freed, a local movie house owner. "Back then, in order to be hip, in order to be literate, in order to be alive, you needed to see films - not just the first runs, but foreign films, revival films, old Hollywood films. You needed to see films in great depth. We called this the film generation." (As a result, the Cambridge scene would spawn a virtual who's who of movie critics - Davld Denby, Stephen Schiff. Owen Gleiberman, and Janet Maslin among them.)

It was Freed, who inadvertently kicked off Harold and Maude mania. He'd booked the Orson Welles Cinema, but was having a rough time in his new role as owner of the Park Square. Then he found Harold and Maude. "It was like manna from heaven, " Freed remembers. "People came back, and it just started building and building. It never seemed to be letting up." Within months, Harold and Maude had been picked up by the Allston, - where it would run for two years.

Across town at the Central Square, booker Bill Holodnak was experiencing the same phenomenon, with a gentle French film about a town that's been taken over by the inmates of a mental asylum. Philippe de Broca's King of Hearts had bombed in its first run, in 1966, so the studio sent it out as a $50 cofeature to help promote de Broca's new film, Give Her The Moon. But as Holodnak remembers, "the audience was just crazy about King; they just started to ooze and gush over it. So we flipped the order of the films, and the same thing happened. We could show this film with anything, and people would flock to it."

King of Hearts ran for almost five years. The Brattle Theatre, and then the Central Square, went through print after print of the film. United Artists had to strike a new one just for the Cambridge engagement. James Cennamo, who sold popcorn and took tickets at the Central Square, remembers King being so popular that Joni Mitchell and her entourage had to bribe the projectionist $200 to get a special showing after the last screening. (Mitchell, though, has no such recollection.)

The blockbuster boom of the '80s and the subsequent home video revolution combined to knock these cult classics off the big screen, but what was it about them that people loved so much? Holodnak writes it off to "weird-ass, simpleminded ritualistic behavior." Freed suspects that their stories contain powerful archetypal messages. For his part, Mike Holland says that Harold and .Maude just makes him feel good. "I see a guy that's dealt with so much, and he copes. I just try to do the same thing.

Those words are spoken in the peace of one of Mike's favorite hangouts: Lexington's Westview Cemetery. It is an older graveyard, with rolling hills and tall, swaying trees. Mike's father is buried here, and here, too, just across the road and under a shade tree, are tombstones marking the final resting place of Mike's girlfriend and their best friend - Brigitte and Meg, killed in another car accident, when Mike was nineteen. "Where that red flower is, that's Meg," he says. "Her mother must have been here recently."

Mike looks past the graves for a moment. "Sadness is there, but you just can't dwell on it, that's the tie-in with Harold and Maude," he says. "You feel bad for the deaths, but you have to feel good about all the other things and go on from there. You can't let their deaths become yours."

Two years after his friends' deaths, Mike met an aspiring

attorney named Jean; On one of their dates, he took her to see his

favorite movie. In its final scene, Harold stands on a hill by the edge of

the sea and jubilantly sends the black hearse, representing his

death-ridden past, over the cliff and tumbling to the surf below. It looks

remarkably like the place where Mike and Jean celebrated their own new

beginning three years ago, on another hill overlooking a different ocean.

The music played at their wedding included Cat Stevens' "Where Do the

Children Play" from Harold and Maude. "Nowadays, I really like

the music," says Mike, who rents the movie two or three times a year.

"I always go away feeling good, and I know that the next day can be

better than yesterday."

BACK TO TOP

Harold and Maude

US (1972): Comedy

Roger Ebert Review: 1.5 stars out of 4

90 min, Rated PG, Color, Available on videocassette and laserdisc

Death can be as funny as most things in life, I suppose, but not the way Harold and Maude go about it. They meet because they're both funeral freaks, and one day their eyes lock over a grave. They fall into conversation after Maude steals Harold's hearse and offers him a ride. Harold drives a hearse, by the way, because he is fascinated by death, particularly his own. So fascinated that maybe the only reason he doesn't kill himself is that suicide would put an end to his suicide fantasies. You can see that Harold is a young man with a problem.

Now Maude, on the other hand, is seventy-nine years young, and has what is known in the trade as a lust for life. She lives in a railroad car, spends her afternoons uprooting city trees and returning them to the forest, and in general is an all-round booster of the life force. She goes to funerals because there is a time to live and a time to die, and she wants to be on time.

The word has gotten out that HAROLD AND MAUDE is the story of a love affair between these two people. It is not, so necrophiliacs please stay cool. It is about how Harold annoys (yes, annoys would be the word) his mother by staging a staggering variety of suicide attempts. Let's see. There's immolation, hanging, whacking off his arm with a meat cleaver, driving his car over a cliff, drowning, and if I missed one, never mind. But his mother is merely annoyed. She takes a morning dip in the swimming pool, for example, and when she comes upon Harold's body floating face down, she merely swims another lap. Talk about exercise freaks.

Harold's mother figures maybe what Harold needs is a little female companionship. She signs him up with a computer dating service, but the girls are sort of put off when he sets himself afire on their date, and things like that. Maude, on the other hand, doesn't seem to mind. As played by Ruth Gordon, she is the same wise-cracking operator out of the side of the mouth that we met in ROSEMARY'S BABY. When a traffic cop stops her for being in possession of a stolen truck, a stolen car, and a stolen shovel, she apologizes and then drives away. When he catches up with her again, she steals his motorcycle. You see what an indomitable sort she is.

Harold is played by Bud Cort, the round-eyed and solemn-mouthed announcer over the PA system in M*A*S*H. He is even rounder and more solemn this time, having perfected a funereal droop of the lower lip. It is hard to get very much animation into a character who is obsessed with his own oblivion, but Cort doesn't even try.

And so what we get, finally, is a movie of attitudes.

Harold is death, Maude life, and they manage to make the two seem so

similar that life's hardly worth the extra bother. The visual style makes

everyone look fresh from the Wax Museum, and all the movie lacks is a lot

of day-old gardenias and lilies and roses in the lobby, filling the place

with a cloying sweet smell. Nothing more to report today. Harold doesn't

even make pallbearer.

BACK TO TOP

Harold and Maude

US (1972): Comedy

Pauline Kael Review

90 min, Rated PG, Color, Available on videocassette and laserdisc

Bud Cort is Harold, a rich, suicidal

introvert with a soft, unformed face—he's 19 but looks younger. Ruth

Gordon is poor but spunky Maude, the wizened 79-year-old woman who's like

a cheerleader for Life. She lives in a railway car, would like to change

into a sunflower, frets over how to save an ailing tree, prankishly steals

vehicles and drives crazily; she advises Harold to "reach out."

In this satirical-whimsical romantic comedy, directed by Hal Ashby from a

script by Colin Higgins, Harold reaches out by falling in love with Maude,

and their love is consummated on the eve of her 80th birthday. Many young

moviegoers have returned to this eccentric film repeatedly (in 1974, one

22-year-old claimed to have seen it 138 times); maybe this is partly

because of its mixture of the maudlin and the highly sophisticated. The

message is not very different from that of HELLO, DOLLY! or MAME, but

Harold's flaccid asexuality (he's like a sickly infant, a limp, earthbound

Peter Pan) and Maude's advanced stage of pixiness give that message a

special freaky quality. And the film has been made with considerable wit

and skill. The early scenes, in which Harold tries out various gruesome

methods of suicide without scaring his unflappable mother (Vivian

Pickles), have a stylized humor. But Ashby has directed eccentrically. The

actors are often seen at a great distance and the dialogue reaches us from

a distance, too; the sound level varies so much that we keep losing the

voices, and Harold's lines often fade away. With Cyril Cusack, Ellen Geer,

and Charles Tyner. Music by Cat Stevens, with mush-minded lyrics.

Paramount.

BACK TO TOP

Harold

and Maude

US (1972): Comedy

CineBooks' Motion Picture Guide Review: 3.5 stars out of 5

90 min, Rated PG, Color, Available on videocassette and laserdisc

HAROLD AND MAUDE was panned by many critics when it was first released,

but there is much in this oddball story to recommend. The film is like no

other and has survived bad notices to become a cult classic.

Synopsis

Teenage depression The son, Harold (Bud Cort), of a wealthy woman, Mrs.

Chasens (Vivian Pickles), lacks friends and receives little attention from

his mother. His frequent depressions cause him to stage more and more

elaborate pranks (fake suicides by hanging, self-immolation, etc.), none

of which impress his mother who is involved with everyone and everything

else. Fascinated by funerals, Harold has an old hearse which he drives to

various cemeteries. At two successive services, he meets a

seventy-nine-year-old woman, Maude (Ruth Gordon), who shares his penchant

for death. She is a memorable character with a great passion for life, no

guilt, and more than a few aphorisms.

Kindred spirits Harold and Maude become great pals and she instills in him a desire to live, to spread his wings, and to enjoy his brief time on earth. As time passes, they share several adventures, including stealing a car, crashing through toll gates, and stealing a tree and replanting it in a forest where it can grow among friends. They are very happy with each other, except for the moments when concentration camp survivor Maude speaks of her late husband and becomes teary.

Harold's mother thinks that Harold should be married and has three women, chosen by computer, come to the estate. Harold frightens off the women, Sunshine (Ellen Geer), Candy (Judy Engles), and Edith (Shari Summers), and shows no interest in any woman besides his octogenarian buddy. Mrs. Chasens enlists her military uncle, Victor (Charles Tyner), to get Harold into the service, but the plan is foiled with Maude's help as Harold pretends to be so sadistic that even Uncle Victor finds it unpalatable.

Advice taken Harold and Maude make love, and he plans to marry her despite the protests of his mother, Uncle Victor, a priest (Eric Christmas), and a psychiatrist (G. Wood). Maude, true to her free-spirit philosophy, celebrates her eightieth birthday by happily saying goodbye to her friends and then taking a fatal dose of sleeping pills. Harold is so stunned that he drives his hearse to a cliff. About to leap, he takes Maude's advice to heart, picks up his banjo and dances up a hill in the final scene.

Background

Initial production This creative film was originally a twenty-minute

script written as a graduate thesis by UCLA student Barry Higgins. He

later showed it to his landlady, the wife of a film producer, and the two

formed their own production company. They made a deal with Paramount in

which Howard Jaffe was originally slated to produce the film, though he

was soon replaced by Colin Higgins and Charles B. Mulvehill.

BACK TO TOP